The therapist said I’m grieving the loss of my father even though he’s still alive. She said it’s a process that can begin early if the person is terminally ill. My father is 88. He was diagnosed with Lewy Body dementia six years ago. He also has advanced heart disease.

In 2015, I began caring for my father. Over the past six years, I’ve watched him decline. In some ways, it has happened slowly. In other ways, quickly.

He’s had various infections and has fallen several times. A few times, he’s been hospitalized. About 18 months ago, he was so sick from a urinary tract infection I wasn’t sure he’d make it out of the hospital. He did but wasn’t the same, not even after a month-log rehabilitation.

He loses something each time he gets sick, especially if he’s hospitalized. He doesn’t bounce back. He survives.

I’ve watched him go from a walker to a wheelchair, from living with us to moving to a facility. From independent living to assisted living to memory care. He has transitioned from (slowly) dressing himself to being dressed, from jeans to sweats, from continence to incontinence, from reading and watching TV to staring.

The biggest change has been in his demeanor, the ponderous, interminable seeping away of the man he once was. His alert blue-green eyes have dulled, his expressive face gone slack.

I remember his big, bold laugh—head back, hand pounding the table. It’s gone now along with so much else, eroded by time and the injustice of this cruel disease.

When I visit my dad now, I’m not sure what will happen. Some days he is ok. He’ll perk up when he sees me. I’ll get a glimpse of my daddy. Other days, he’s a shell. He’s physically present but not really there.

Those days are the hardest because my father has been replaced by someone else.

I don’t think he remembers my name, but he usually knows who I am. Not always though. Some days it takes him a bit, such as earlier this week. I walked over, put my hand on his shoulder and greeted him, my mask down. He turned and looked at me, his eyes unfocused, confused. They swept past me, looking for a place to hand.

“It’s Eileen, Dad, your daughter.” I said. It was the first time I’ve had to say those words. I thought I was prepared for them but they sounded wrong coming out of my mouth.

“Oh hi baby,” he said, a flicker of light coming into his eyes.

He was wearing sweat pants littered with bits of food. His hands were stained with something. I brushed away crumbs and took my hand sanitizer from my purse, pouring a little on his hands.

“Ow,” he said.

“I’m sorry, Dad. I’m trying to clean you up. Did you hurt your hand?”

“It hurts all the time,” he said.

The fingers on his right hand looked bent and swollen.

“Did you have a good breakfast?” I said.

“I don’t know,” he said.

Even just a few months ago, he remembered meals. He liked breakfast sausage and would comment on it. But the last few weeks, he hasn’t remembered eating.

I searched for something else. “How are you doing, Dad? Did you sleep ok?”

“Ok until we do that other thing,” he said. “They’re going to that place.”

He spoke a little more, the words gibberish, a mixture of sounds and colliding snippets. Once I could tell by the inflection in his voice he was asking a question, but it may as well have been in another language. It sounded like nonsense, like what buzzing did that whatsit tapped doshie say?

I searched again. “Do you want to hear some music, Dad?”

“Yes!” he said, light coming back into his eyes. “Play that one.”

I wasn’t sure but had an idea. On the last few visits, he seemed the happiest—the most alive—during “What a Fool Believes” by the Doobie Brothers. Each time he responded as if it were new but also familiar.

How can that be? How can something be both new and familiar? I don’t know. It’s just another murky part of dementia. But I see it on his face, in the way his head pops up and his eyes brighten for a moment. A window opens in his mind.

I wonder if it’s like meeting someone and sensing you’ve known the person a long time. Do they remind you of someone else? A positive experience? No specific memory is there, but the feeling is powerful. It has happened to me. A pleasant sensation—a kind of warmth—infused me. I felt drawn to the new person without knowing why.

My father is drawn to the music of his past, songs he can’t recall but still remembers.

One day last week I played “Help Me Make it Through the Night” by Sammy Smith. Her version has always been his favorite. As it began to play he said, “Oh yes” and then closed his eyes. He went somewhere else, a place that looked so tender. I felt like an intruder.

I played a few more songs. After he opened his eyes, his chin dropping a little. He looked spent. He was tired. It was time for me to go.

Our visits have changed from a year ago, from four or five months ago. They’re music sessions now. We share songs and space, not much else. Sometimes he cries and I’ll squeeze his hand. He’ll open his eyes and pat my hand in return, occasionally looking surprised to see me.

Then I’ll play an upbeat song like “Family Tradition” by Hank Williams Jr., and he’ll laugh and sing/hum along. I’ll sing with him. In those moments, he seems happy.

Or maybe that’s what I want to believe, because other times he is agitated. He’s always been a worrier, but dementia has magnified it. Sometimes there’s a brittle edge to him. He’s angry at someone who tried to kill him. “That a—hole,” he’ll say. Underneath, there is something else. Sorrow?

During those times, I don’t know how to comfort him. The other day, I prayed for him. I drew my chair close, our knees touching, and held his hand. After our prayer I read from the Bible, Matthew 11:28-30:

“Come to me, all of you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke and learn from me, because I am lowly and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light.”

Another day was different. I brought a few pictures I found tucked away in a box at home.

There were dozens of loose photos, some faded and blurry, others more clear. I spent hours combing through them, spreading them out on the table.

I looked for pictures of my father when he was young and vibrant. There weren’t as many because he was usually the one holding the camera. But I found a few probably taken by my mother, because people’s heads were cut off or the pictures were at weird angles.

Some of the photos looked so old—yellowish and blurry. My mother was young and lovely with teased hair and perfectly arched brows. There was no editing of photos back then, no deleting the bad ones. You took your film to the camera store and waited to see what would come back. You might get four shots of a coffee table or someone in silhouette because the flash didn’t work.

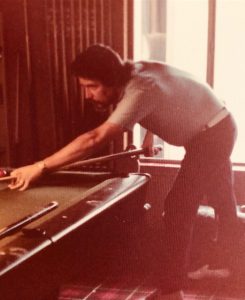

In one picture the 1970s is on display. My father is standing in front of an orange-striped wall. He has a mustache and his dark hair—abundant, lush—is brushed back from his face. He’s wearing a green flowered shirt and smiling broadly. He looks handsome and vital.

In an earlier black and white business photo, he has a flattop and is clean-shaven. He’s standing with a group of men, all wearing suits and skinny ties. He’s in his 30s but looks a decade younger. One of the men is my uncle. The picture was taken when my dad worked with him in Alaska.

I take these and a few other photos to my next visit, hoping he’ll be reminded of happier times.

But he doesn’t recognize anyone except himself. He thinks my oldest sister is me and is puzzled by his brother. Something flickers across his face when he sees his favorite niece, but he can’t name her. He doesn’t seem aware or upset he can’t remember. He’s just blank.

I tell myself blank is better. He doesn’t know what he doesn’t know. The stress isn’t his; it’s mine. So why do I struggle with it so much? Why do I feel defenseless against searing pain?

Perhaps it’s the suddenness of it, the way it comes out of nowhere and smacks me hard and fast. I’m caught off balance. One second I’m playing music and singing with my dad, my hand on his shoulder. The next I’m biting my lip, tears streaming down my face. I turn away so he can’t see me, afraid my emotion will upset him. I don’t know why I’m crying, except something within me aches so much.

Those are the hardest times, because they hit me sideways—random, savage attacks. And even after I leave, I’ll feel shaky for hours. I’ll close my eyes to sleep and my mind will flash pictures of my dad’s shrunken frame slumped in his wheelchair.

I’ll close my eyes again and see the faces of other residents, such as two women who tried to follow me out as I left one day last week. I’ll see them furiously shuffling toward the door as it buzzes open, and then a staff member taking their arm and guiding them back. I’ll remember that buzzing–the sound of my freedom and their captivity.

Recently a friend mentioned that long ago, grieving was acknowledged. After a family member died, women would wear black and withdraw from society for a year. They were given time to process their feelings. They were allowed to be sad. I’ve seen this in period movies and TV shows.

But not now. It’s a different time and a different world. People aren’t supposed to be sad—at least not for long. They need to be fixed.

I’ve heard I should take antidepressants for my depression, sleeping pills for my insomnia, perhaps Xanax or medical marijuana for my anxiety. I should try yoga, walking or a hobby. I need better self-care and more “me” time.

I should be happy for my dad’s good days and on the bad ones, grateful for this “rewarding” time with him.

I wonder what happens when sorrow begins early, when it’s more like a leaking faucet than a burst pipe. No gushing water, just a tiny drip. But it never stops. Drip, drip, drip.

If I wore black, would it help? Would people let me cry? Would there be consolation in easing into it, in gradually letting it out? I want to think so, but I’m not sure it would help.

Some days I think there won’t be any relief until I break.